The Group of Seven (G7)

by Zachary Laub

Introduction

The Group of Seven (G7) is an informal bloc of industrialized democracies—France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, and Canada—that meets annually to discuss issues of common interest like global economic governance, international security, and energy policy. Proponents say the forum's small and relatively homogenous membership promotes collective decision-making, but critics note that it often lacks follow-through and that its membership excludes important emerging powers. Russia belonged to the forum from 1998 through 2014—then the Group of Eight (G8)—but the other members suspended their cooperation with Moscow after its annexation of Crimea in March of that year.

Membership

France, West Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States formed the Group of Six in 1975 (Canada joined the following year) to provide a venue for the noncommunist powers to address pressing economic concerns, which at the time included inflation and a recession sparked by the OPEC oil embargo. Cold War politics invariably entered the group's agenda.

The European Union has participated fully in the G7 since 1981 as a "nonenumerated" member. It is represented by the presidents of the European Council, which represents the EU member-states' leaders, and the European Commission, the EU's executive body.

There are no formal criteria for membership, but participants are all highly developed democracies. The aggregate GDP of G7 member states makes up nearly 50 percent of the global economy.

Unlike the United Nations or NATO, the G7 is not a formal institution with a charter and a secretariat. Instead, the presidency, which rotates annually among member states, is responsible for setting the agenda and arranging logistics. Ministers and envoys, known as sherpas, hammer out policy initiatives at meetings that precede the annual summit of national leaders.

(Source: The Group of Seven (G7) by Zachary Laub, http://www.cfr.org/staff/b19316)Brazil, Russia, India And China - BRIC

An acronym for the economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China combined. The general consensus is that the term was first prominently used in a Goldman Sachs report from 2003, which speculated that by 2050 these four economies would be wealthier than most of the current major economic powers.

The BRIC thesis posits that China and India will become the world's dominant suppliers of manufactured goods and services, respectively, while Brazil and Russia will become similarly dominant as suppliers of raw materials. It's important to note that the Goldman Sachs thesis isn't that these countries are a political alliance (like the European Union) or a formal trading association - but they have the potential to form a powerful economic bloc. BRIC is now also used as a more generic marketing term to refer to these four emerging economies.

Due to lower labor and production costs, many companies also cite BRIC as a source of foreign expansion opportunity.

Due to lower labor and production costs, many companies also cite BRIC as a source of foreign expansion opportunity.

(Source: http://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bric.asp)

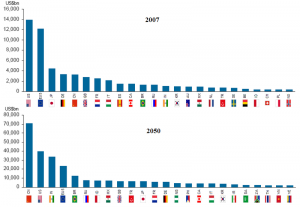

BRIC Countries’ Path to 2050

A country’s population and demographics, among other factors, directly affect the potential size of its economy and its capacity to function as an engine of global economic growth and development. As early as 2003, Goldman Sachs forecasted that China and India would become the first and third largest economies by 2050, with Brazil and Russia capturing the fifth and sixth spots. The chart below shows a more recent forecast of the world ranking of the biggest economies in the year 2050. (Click on the image below to view the full-size chart in a separate tab or browser window.)

One BRIC, Two BRICs

The BRIC designation was first coined by Jim O’Neil of Goldman Sachs in a 2001 paper titled “The World Needs Better Economic BRICs.” The BRIC countries have since gone on to meet and seek out opportunities for cooperation in trade, investment, infrastructure development and other arenas. China invited South Africa to join the group of BRIC nations in December, 2010 and hosted the third annual BRICs Summit in April, 2011.

Key Indicators and Statistics

Economic Growth and Development of the BRICs

From 2000 to 2008, the BRIC countries’ combined share of total world economic output rose from 16 to 22 percent. Together, the BRIC countries accounted for 30 percent of the increase in global output during the period.

To date, the scale of China’s economy and pace of its development has out-distanced those of its BRIC peers. China alone contributed more than half of the BRIC countries’ share and greater than 15 percent of the growth in world economic output from 2000 to 2008. The chart above on key development indicators for the BRIC countries shows the sharp contrast in GDP, merchandise exports and the UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) between China and the other BRIC countries.

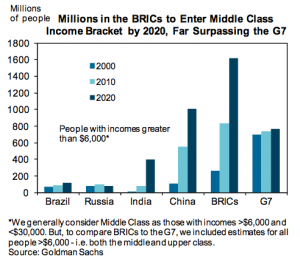

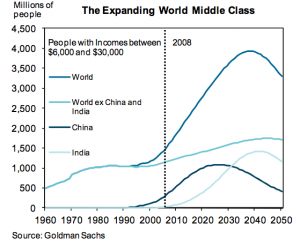

Growing BRIC Middle Class

The rapid economic growth and demographics of China and India are expected to give rise to a large middle class whose consumption would help drive the BRICs’ economic development and expansion of the global economy. The charts below depict how the increase in the middle class population of the BRIC countries is forecasted to more than double that of the developed G7 economies. (Click on the images below to view the full-size charts in separate tabs or browser windows.)

Science and Technology in the BRICs

The BRIC countries of China, India and Brazil account for much of the dramatic increase inscience research investments and scientific publications. Since 2002, global spending on science R&D has increased by 45 percent to more than $1,000 billion (one trillion) U.S. dollars. From 2002 to 2007, China, India and Brazil more than doubled their spending on science research, raising their collective share of global R&D spending from 17 to 24 percent.

China’s development planning has targeted a number of scientific fields and related industries, including clean energy, green transportation and rare earths, among others. Since 1999, China’s spending on science R&D has grown 20 percent annually to more than $100 billion. By 2020, China plans to invest 2.5 percent of GDP in science research.

(Source: BRIC Countries – Background, Latest News, Statistics and Original Articles, http://www.globalsherpa.org/bric-countries-brics)

No comments:

Post a Comment